Uncivil liberties

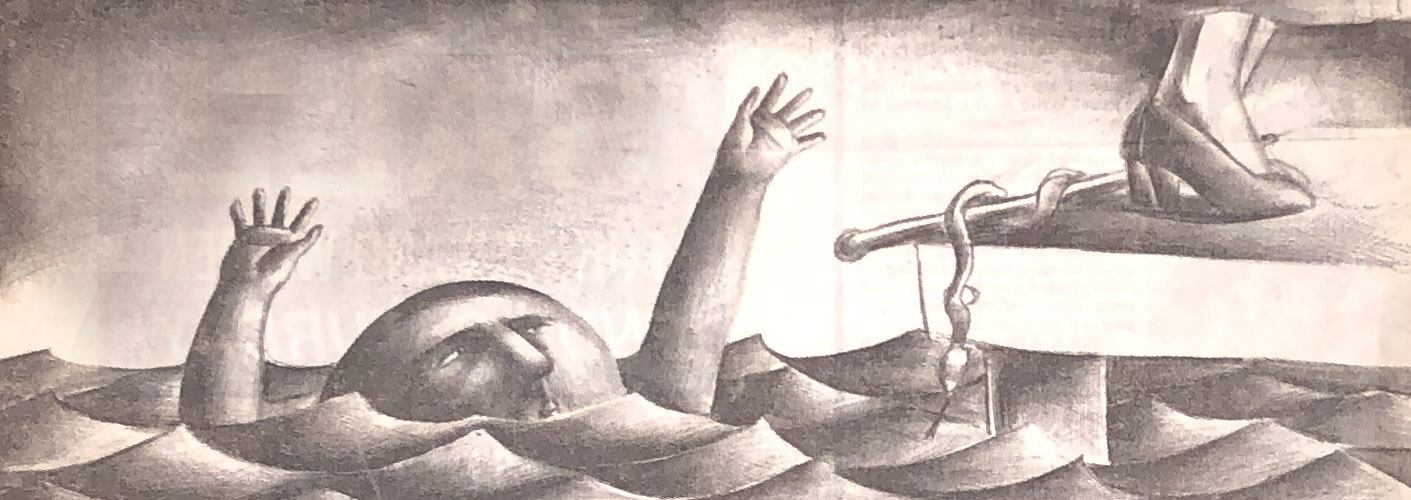

Far from respecting civil liberties, legal obstacles to treating the mentally ill limit or destroy the liberty of the person.

The public is growing increasingly confused by how we treat the mentally ill. More and more, the mentally ill are showing up in the streets, badly in need of help. Incidents of illness-driven violence are reported regularly, incidents which common sense tells us could easily have been avoided. And this is just the visible tip of the greater tragedy – of many more sufferers deteriorating in the shadows and, often, committing suicide.

People asked in perplexed astonishment: ” Why don’t we provide help and treatment, when the need is so obvious?” Yet every such cry of anguish is met with the rejoinder that unrequested intervention is an infringement of civil liberties.

This stops everything. Civil Liberties, after all, are a fundamental part of our democratic society. The rhetoric and lobbying results in legislative obstacles to timely and adequate treatment, and the psychiatric community is cowed by the anti-treatment climate produced.

Here is the Kafkaesque irony: Far from respecting civil liberties, legal obstacles to treatment limit or destroy the liberty of the person.

The best example concerns schizophrenia. The most chronic and disabling of the major mental illnesses, schizophrenia involves a chemical imbalance in the brain, alleviated in most cases by medication. Symptoms can include confusion; inability to concentrate, to think abstractly, or to plan; thought disorder to the point of raving babble; delusions and hallucinations; and variations such as paranoia.

Untreated, the disease is ravaging. Its victims cannot work or care for themselves. They may think they are other people – usually historical or cultural characters such as Jesus Christ or John Lennon – or otherwise lose their sense of identity. They find it hard or impossible to live with others, and they may become hostile and threatening. They can end up living in the most degraded, shocking circumstances, voiding in their own clothes, living in rooms overrun by rodents – or in the streets. They often deteriorate physically, losing weight and suffering corresponding malnutrition, rotting teeth and skin sores. They become particularly vulnerable to injury and abuse.

Tormented by voices, or in the grip of paranoia, they may commit suicide or violence upon others. (The case of a Coquitlam boy who killed most of his family is only one well-publicized incident of such delusion-driven violence.) Becoming suddenly threatening or bearing a weapon, say a knife – because of a delusionally perceived need for self-protection – the innocent schizophrenic may be shot down by police.

Depression from the illness, without adequate stability – often as the result of premature release – is also a factor in suicides.

Such victims are prisoners of their illness. Their personalities are subsumed by their distorted thoughts. They cannot think for themselves and cannot exercise any meaningful liberty. The remedy is treatment – most essentially, medication. In most cases, this means involuntary treatment because people in the throes of their illness have little or no insight into their own condition. If you think you are Jesus Christ or an avenging angel, you are not likely to agree that you need to go to the hospital.

Anti-treatment advocates insist that involuntary committal should be limited to cases of imminent physical danger – instances where a person is going to do serious bodily harm to himself or to somebody else. But the establishment of such “dangerousness” usually comes too late – a psychotic break or loss of control, leading to violence, happens suddenly. And all the while, the victim suffers the ravages of the illness itself, the degradation of life, the tragic loss of individual potential.

The anti-treatment advocates say: “If that’s how people want to live (babbling on a street corner, in rags), or if they wish to take their own lives, they should be allowed to exercise their free will. To interfere – with involuntary committal – is to deny them their civil liberties.” As for the tragedy that follows from this dictum, well, “That’s the price that has to be paid if society is to maintain its civil liberties.”

Whether or not anti-treatment advocates actually voice such opinions, they seem content to sacrifice a few lives here and there to uphold an abstract doctrine. Their intent, if noble, has a chilly, Stalinist justification – the odd tragedy along the way is warranted to ensure the greater good. The notion that this doctrine is misapplied escapes them. They merely deny the nature of the illness.

Health Minister Elizabeth Cull appears to have fallen into the trap of this juxtaposition. She has talked about balancing the need for treatment and civil liberties, as if they were opposites. It is with such a misconceptualization that anti-treatment lobbyists promote legislation loaded with administative and judicial obstacles to involuntary committal.

The result, inadvertently for Cull, Attorney-General Colin Gabelmann (as regards guardianship legislation) and the government, will be a certain number of illness-caused suicides every year, just as surely as if those people were lined up annually in front of a firing squad. Add to that the broader ravages of the illness, and keep in mind the manic depressives who also have a high suicide rate.

A doubly ironic downstream effect: the inappropriate use of criminal prosecutions against the mentally ill, and the attendant cruelty of committal to jails and prisons rather than hospitals. B.C. Corrections once estimated that almost one third of adult offenders and close to half of the young offenders in the provincal correction system have a diagnosable mental disorder. Clinical evidence has now indicated that allowing schizophrenia to progress to a psychotic break lowers the possible level of future recovery, and subsequent psychotic breaks lower that level further – in other words, the cost of withholding treatment is permanent damage.

Meanwhile, bureaucratic road-blocks, such as time consuming judicial hearings, are passed off under the cloak of “due process” – as if the illness were a crime with which one is being charged and hospitalization for treatment is a punishment. Such cumbersome restraints ignore the existing adequate safeguards – the requirement for two independent assessments and a review panel to check against over-long stays.

How can so much degradation and death – so much inhumanity – be justified in the name of civil liberties? It cannot. The opposition to involuntary committal and treatment betrays a profound misunderstanding of the principle of civil liberties. Medication can free victims from their illness – free them from the Bastille of their psychoses – and restore their dignity, their free will and the meaningful exercise of their liberties.

By Herschel Hardin — a West Vancouver author and consultant.

He was a director of the BC Civil Liberties Association from 1965-1974

and has been involved in defence of liberty and free speech through his

work with Amnesty International. One of his children has schizophrenia.